Understanding the Role of the Adrenal Glands

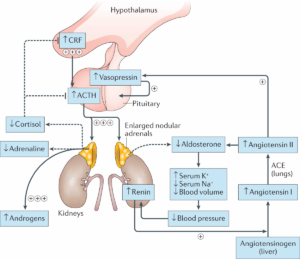

The adrenal glands produce three main hormones. Cortisol helps the body respond to stress, illness, and injury while also playing a key role in maintaining blood sugar, energy levels, and blood pressure. Aldosterone is essential for regulating the body’s balance of salt and water, which in turn helps maintain normal blood pressure. Androgens, which are typically considered male sex hormones like testosterone, are produced in both sexes and contribute to growth, puberty, and reproductive function.

In CAH, a missing or defective enzyme most often 21-hydroxylase disrupts the adrenal glands’ ability to produce sufficient cortisol and/or aldosterone. In response to low cortisol levels, the pituitary gland signals the adrenal glands to produce more hormones, which leads to an overproduction of androgens and the resulting hormonal imbalance.

Types of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

There are two primary forms of CAH: Classic CAH and Nonclassic CAH, each varying in severity and symptoms.

Classic CAH is the more severe form and is typically diagnosed at birth or shortly after through routine newborn screening. It is divided into two subtypes. The first, Salt-Wasting CAH, is the most serious and results from a severe deficiency in aldosterone. This causes the body to lose large amounts of sodium through urine, leading to dehydration, low blood pressure, electrolyte imbalances, and potentially life-threatening adrenal crises. The second subtype, Simple-Virilizing CAH, affects cortisol production without causing significant salt loss. However, excess androgen production still leads to abnormal sexual development and early onset of puberty-related changes.

Nonclassic CAH is a milder and more common form that often goes unnoticed until later in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood. It does not typically cause adrenal crises, but it can result in signs of androgen excess such as early puberty, acne, irregular menstrual cycles, hirsutism (excess body or facial hair in females), and infertility. In some cases, individuals may have no symptoms at all.

Very rare forms of CAH, caused by deficiencies in other enzymes such as 11-hydroxylase, also exist but occur far less frequently.

Who is Affected by CAH?

CAH can affect individuals of all genders, ethnic backgrounds, and ages. The condition follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, meaning that a child must inherit one faulty gene from each parent in order to develop the disorder. People who inherit only one defective gene are carriers and usually do not show any symptoms.

Classic CAH affects approximately 1 in every 10,000 to 15,000 individuals in the United States and Europe, while nonclassic CAH is more common and may affect as many as 1 in every 100 to 200 people.

Symptoms of CAH

The symptoms of CAH vary depending on the type and severity of the disorder and are influenced by biological sex.

In females with classic CAH, excess androgen exposure in the womb can lead to ambiguous genitalia at birth. This means that while the internal reproductive organs (such as ovaries and uterus) are typically female, the external genitalia may appear more typically male due to the influence of androgens. In males, the condition may be less immediately apparent at birth but can result in an enlarged penis or signs of early puberty in childhood.

Children of both sexes may experience rapid growth, early development of pubic and body hair, acne, deepening of the voice, and early puberty. Over time, untreated CAH can lead to short adult height due to premature closure of growth plates.

In salt-wasting CAH, the most severe form, symptoms can include severe dehydration, low blood pressure, low sodium levels (hyponatremia), low blood sugar, and, if left untreated, adrenal crisis, which can be life-threatening.

In nonclassic CAH, symptoms are usually milder and appear later. These may include irregular or absent menstrual cycles, hirsutism, acne, male-pattern baldness, early puberty, and infertility in some females.

Causes and Genetic Background

CAH is most commonly caused by mutations in the CYP21A2 gene, which leads to a deficiency in the 21-hydroxylase enzyme. This enzyme is necessary for producing cortisol and aldosterone. In rare cases, CAH may be caused by deficiencies in other adrenal enzymes, such as 11-hydroxylase. The condition is inherited genetically, and individuals with a family history of CAH or who are carriers of a mutated gene are at greater risk of passing the condition to their children.

Diagnosis of CAH

Diagnosis often begins with newborn screening, a standard procedure in many countries that involves a blood test to check for abnormal hormone levels. If a baby has a family history of CAH, prenatal testing may be considered through procedures such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling.

For nonclassic CAH, diagnosis typically occurs later in life when symptoms emerge. Doctors may conduct blood and urine tests to measure hormone levels and hormone metabolites. Genetic testing can confirm mutations in the CAH-related genes. A physical examination and growth assessments may also be used in children to support diagnosis.

Treatment and Management

Although CAH cannot be cured, it is a manageable condition. Treatment aims to correct hormonal imbalances, prevent adrenal crises, and support normal development.

Individuals with classic CAH usually require lifelong hormone replacement therapy, including glucocorticoids to replace cortisol and mineralocorticoids to replace aldosterone. Salt supplements may also be needed, especially in infants with salt-wasting CAH. During times of illness or physical stress, medication doses often need to be increased to prevent adrenal insufficiency.

Surgical intervention may be considered for infants with ambiguous genitalia. This is typically done between two to six months of age, but some families may choose to delay surgery until the child is older.

For nonclassic CAH, treatment depends on symptom severity. Some individuals require no treatment at all, while others may benefit from low-dose glucocorticoids to manage specific symptoms such as irregular menstruation, acne, or excess hair growth. Long-term medication may not be necessary in all cases.

Potential Complications

If left untreated, classic CAH can lead to serious complications, including electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, irregular heart rhythms, and potentially fatal adrenal crises. In females, ongoing exposure to excess androgens can lead to irreversible masculinization, infertility, and psychosocial challenges. Males may also experience short stature and early puberty. Surgical interventions can carry risks such as infection, scarring, and the possibility of needing additional surgeries later in life.

Prognosis and Outlook

With early diagnosis and appropriate management, individuals with CAH can live healthy, fulfilling lives. Those with classic CAH typically require daily medications and regular monitoring of hormone levels. While fertility may be affected in some cases, many people with CAH can conceive with medical assistance. Emotional and psychological support is also important, especially for individuals facing gender identity concerns or dealing with the social implications of the condition.

Prevention and Genetic Counseling

Because CAH is a genetic disorder, it cannot be prevented. However, genetic counseling is recommended for individuals or couples with a family history of CAH or who are known carriers of the condition. Through genetic testing and counseling, parents can better understand their risk of having a child with CAH and explore options for prenatal diagnosis.

Living with CAH: What You Should Know

In such cases, a healthcare provider may recommend working with a dietitian or nutritionist to develop a tailored eating plan that helps manage weight while ensuring the body receives all necessary nutrients. Regular physical activity is also encouraged, as it not only helps control weight but also improves cardiovascular health and reduces stress important factors for individuals with hormone-related conditions.

Psychological and emotional support is just as vital as medical treatment. Children and adults living with CAH may face emotional challenges related to body image, gender identity, or social interactions, particularly if they experienced ambiguous genitalia at birth or undergo lifelong hormone therapy. Access to counseling, peer support groups, and mental health professionals can significantly improve quality of life, self-esteem, and emotional resilience.

Education and awareness are powerful tools for individuals with CAH and their families. Understanding the condition, its management, and how to respond during medical emergencies bsuch as an adrenal crisis is essential. Many people with CAH carry a medical alert bracelet or card that details their diagnosis and emergency treatment instructions, which can be life-saving in critical situations.

For families with young children diagnosed with CAH, building a strong relationship with a pediatric endocrinologist and ensuring proper follow-up care throughout growth and puberty is crucial. Puberty, menstruation, sexual development, and fertility should be openly discussed with healthcare providers as the child grows, so care can be adjusted to fit changing needs.

Access to specialist care is also important when planning pregnancy. Women with CAH who wish to conceive should be under the care of a reproductive endocrinologist or a multidisciplinary team that can help optimize hormone levels and support fertility. While fertility may be reduced in some forms of CAH, many women are able to conceive with proper treatment and hormonal management.

In some countries, CAH particularly the classic, salt-wasting form may qualify as a disability if it significantly affects daily functioning or requires ongoing, intensive medical treatment. In these cases, individuals and families may be eligible for social or financial support programs. It’s helpful to consult local healthcare and legal professionals for guidance on available resources and support networks.

Final Thoughts

Being diagnosed with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia can be overwhelming, especially for parents who are navigating their child’s diagnosis and treatment options. However, advancements in medical science, genetic testing, hormone therapy, and psychosocial support have significantly improved outcomes for individuals living with CAH.

Early diagnosis, often through newborn screening, allows for timely treatment and can prevent life-threatening complications such as adrenal crises. For many individuals, CAH becomes a manageable part of life with proper medication, routine follow-up, and education about the condition.

Living with CAH may involve unique challenges, including fertility issues, body image concerns, or the need for lifelong hormone therapy. But with a strong care team, emotional support, and ongoing monitoring, most individuals with CAH can live full, healthy, and productive lives.

For families planning to have children, genetic counseling can offer peace of mind by helping to understand risks and explore options for prenatal diagnosis or early intervention. As knowledge continues to grow in the fields of endocrinology and genetics, the outlook for people with CAH becomes increasingly hopeful.

Understanding the condition, advocating for proper care, and connecting with others in the CAH community can empower individuals and families to thrive in the face of this rare but treatable disorder.